It seems to me that the term ‘adverbial’ needs to be removed from the synthetic-grammar lexicon, because it is not transparent and it is often unclear as to what is an adverbial and what is not. In the current conventional approach to explaining the synthetic grammar of English, if something is clearly not a subject, an object, a verb or a complement, then we have to assess if it’s an adverbial. Given the general lack of clarity as to what an adverbial is, we may be uncertain as to whether the sentence component we are focusing on is an adverbial or not. If we decide it is not, then no functional-category term is left by which it can be described. What that means is that certain elements in a sentence can be left in terminological and conceptual limbo.

It occurs to me that there may, just possibly, be a solution to the problems here through using, instead of adverbial, the categories of adjunct, disjunct and conjunct. Maybe the term adverbial is too vague and, so, having in its place more individually confined terms may be a solution. Maybe, these individually confined terms will, together, cover a greater terrain of functional exponents and, even, successfully and reliably subsume everything that is not categorisable within the other terms of subject, object, verb and complement. So, what are these more individually defined categories? How are they defined?

What are adjuncts, disjuncts and conjuncts?

Adjuncts

As it happens, adjuncts are variously defined, but let’s try and draw out some relatively common threads from when they are defined. One can say about adjuncts that they are mostly, but not always, seen as a subcategory of the adverbial – with the adverbial itself being seen generally as what describes place, time, manner, co-textual connections, the speaker’s attitude etc. Adjuncts are variously seen as a dispensable part of the sentence but also as, in some sense, integral to the sentence. What this seems to mean, in practice, is that adjuncts can be left out of a sentence but, if they are left out, the sentence still has all the characteristics of being a complete sentence while, counter-intuitively perhaps, they are key to the overall meaning of the sentence and, in that sense, integral. For example, look at this sentence:

I saw Ted in his office yesterday afternoon.

Here, the expressions in his office and yesterday afternoon are said to be adjuncts (describing place and time); if they are left out of the sentence, the sentence is still complete and satisfactory as a sentence (as in I saw Ted) and, thus, they are seen as dispensable. But, at the same time, they are key to the overall meaning of the sentence, and thus integral. They are integral in that the sentence may make little or no sense in a given context without them being present. For example, let’s say someone muses to us with a note of concern in her voice:

I haven’t seen Ted here in the Institute for weeks.

Let’s say we reply:

I saw Ted.

Our interlocutor may feel a bit nonplussed and unreassured. She might be thinking: ‘Is Ted alive?’ ‘Is Ted ill?’ ‘Is Ted on holiday?’ ‘Has Ted resigned?’

Disjuncts

Disjuncts, by contrast, indicate the speaker’s or writer’s attitude to the content of the sentence, as in:

Unfortunately, he didn’t get to the meeting on time.

The disjunct here is unfortunately, and it expresses the fact that his failure to get to the meeting on time was, in the speaker’s view, unfortunate. Similarly to adjuncts, disjuncts are seen as dispensable in that the sentence, without them, is still grammatically acceptable and viable as a sentence, as in He didn’t get to the meeting on time. In contrast to adjuncts though, disjuncts are not integral to the sentence; so, for example, if the disjunct unfortunately is left out of the sentence, there is very little loss to the propositional content of the sentence.

Conjuncts

Conjuncts generally connect a sentence to previous parts of the text and show the relationship between the two. Here are two examples with the conjuncts however and therefore:

A) Alan’s proposal was brilliant. However, it would cost a lot of money to effect and it was very uncertain as to whether it would work.

B) The situation was desperate and there were no other equally interesting ideas on offer. Therefore, they decided to approve and fund his plan.

Clearly, as with adjuncts and disjuncts, conjuncts are dispensable in that the sentence is still a grammatically adequate sentence without them, as in it would cost a lot of money … and they decided to approve and fund his plan. But, are they integral to the meaning of the sentence or not? I think they are variable in this respect and a lot depends on what we know of the context of the sentence. Look at this example:

It was raining. They went for a run.

Now, if we know that they only like to run in the rain because they find it more refreshing, then there feels to be no need for a conjunct here. But, if we don’t know that, then the two sentences together feel somewhat unclear semantically, somewhat unformed in their propositional content. Alternatively, if we put in two conjuncts to enforce the intended meaning, thus:

It was raining. But, they went for a run nonetheless.

then now, we know that it was odd for them to go running in the rain but they did it nonetheless. If we leave out those two conjuncts, then the meaning is unclear and, so, it would seem that these two conjuncts here are quite integral to the meaning of the text when we have little context of knowledge to refer the sentences against.

What a mess!

It seems to me that there are a number of problems with the tripartite distinction between adjunct, disjunct and conjunct, which I will list here.

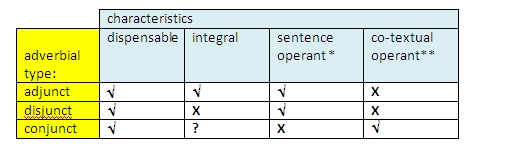

1) This set of distinctions operates on a number of separate parameters, as shown in this table.

* operating semantically within the sentence

** operating semantically across sentences

My own feeling is that multiple parameters, such as these shown in blue highlight, are intellectually and conceptually messy. It’s much better to have one or, at most, two parameters determining the contours of a conceptual distinction; having more than that tends to mean that none of the individual parameters in themselves are adequate to explain the required distinction, as is the case here. It’s also better for parameters to be working in one area but, here, we have two parameters (dispensability and ‘integralness’) working within the context of grammar, and two parameters (sentence-operancy and co-textual operancy) working within the context of discourse. To have sets of parameters in relation to the same focus of interest working within different areas of the language is messier still. It tends to mean that the parameters are inelegant (i.e. intellectually ‘fuzzy’) and, therefore, difficult to understand and difficult to use.

2) The parameters of this set of distinctions have no explanatory value. If, for the moment, we take the notion of the adverbial as superordinate to the notions of adjunct, disjunct and conjunct, then it has to be said that issues of dispensability and ‘integralness’ are not of relevance to the adverbial. Given that English is a distributive language where the syntactic function of the parts of the sentence (e.g. subject, object, verb) are largely determined by their position in the sentence and given that the only part(s) of the sentence that may be moved around within a declarative statement are the adverbial(s), then the key thing we need to know about each adverbial is how much flexibility it has in terms of where it can be placed within the sentence. Flexibility of position is quite distinct from issues of ‘integralness’ and dispensability. Most adverbials, by default, go at the end of the sentence but they can be used elsewhere within the sentence. Indeed, conjuncts tend to go at the front but not always. And, disjuncts can go at the front, in the middle or at the end of the sentence. Adjuncts tend to go at the end, but they too can be used in other positions in the sentence. Although it can be fun perhaps categorising adverbials within these three categories, it is a pointless activity in relation to the key activity of indicating what kinds of adverbial can go where in the sentence. What we have here is a set of distinctions that are another grammatical layer without grammatical use, whereas what we need is not another grammatical layer but a semantic layer because adverbials differ in terms of their sentence-position flexibility in relation to their semantics. One of the great mistakes that can be made within grammar modelling is in creating grammatical sub-divisions, when what is needed is to move out of grammar and to go into semantics. A key part of the art of grammar modelling is knowing when to go directly into semantics and when not to.

3) The adjunct is something of a variably used term and this creates confusion. As shown above, the term is used as a subcategory of adverbial, when the adverbial is considered superordinate to the adjunct – not always the case, as we shall see. But, the term adjunct is also used for something that adds to something else. This second meaning is the main way in which it is defined and exemplified in the OED*. Here the term is not defining something necessarily within the sentence parts of the synthetic grammar of a sentence. Instead, it can describe something working as an addition within the phrase. So, for example, in the combination of very cold weather, cold is seen as an adjunct in that it modifies weather. (Interestingly, something that modifies an adjunct [e.g. here very] is not seen, by linguists such as O Jespersen, as an adjunct but as a subjunct, a modifier of an adjunct.) So, in this use of adjunct, it is not working at the synthetic grammar level but at a syntactic level within combinations of words that are a unit of meaning. When linguists then start talking about adverbial adjuncts, it is often unclear, given the huge semantic flexibility of noun phrases in English, as to whether they are referring to something that is (1) an adjunct (a general category of something that joins to something else) of an adverbial nature (a sub-category) or (2) an adverbial (general category within the synthetic grammar) of an adjunctive nature (a sub-category in contrast with disjunct and conjunct). The lack of a generally accepted precise signification for the term adjunct renders it of little value in any synthetic-grammar categorisation system.

4) A similar problem is apparent with the term conjunct. Because it looks similar in form to the term conjunction, some grammarians lose sight of the fact that conjuncts operate within the synthetic grammar and conjunctions operate within the analytic grammar. I have seen one internet-published grammarian state that the difference between the two is somewhat spurious and technical. Well, no, it’s not. So, perhaps conjunct is not a useful term as it tends to give rise to this kind of conflation of different levels of the grammar. Though, in the past, I have said that similarity of terms within different aspects of the grammar should not lead us against using them on one or the other level, I am slightly questioning that now as it can lead to such significant errors of understanding, such as the one described directly above.

5) Because of the degree of uncertainty that exists as to what exactly an adverbial is, sometimes the notion of the adjunct is set up in distinction with the adverbial and not as a subcategory of it. The Cambridge Dictionary online, though it does not define the adverbial, sets up a contrast between the adverbial and the adjunct as if both are on the same level of analysis within the language. It states that an adjunct is dispensable from a sentence, as shown above, but that an adverbial is not. It explains this contrast by offering an example of an indispensable adverbial after the verb put (= ‘place’); the adverbial cannot be removed from the sentence if the sentence is to retain some completeness as a sentence. Look at this example of that:

She put some flowers in a vase hurriedly.

Here, in a vase is being defined as an adverbial because it is indispensable, in that the sentence without it is no longer perceivable as a complete sentence:

* She put some flowers hurriedly.

But, hurriedly is an adjunct because it is dispensable, as the sentence without it is still an effective sentence:

She put some flowers in a vase.

This perception of the adverbial is the same as that defined as the adverbial complement, discussed previously, where a complement is seen, for some reason, as something that necessarily completes something else. As far as I can figure out, adverbials are only indispensable after the verbs put. It seems strange to set up a whole grammatical category for such a small fraction of all possible instances within the language. It’s also strange to see a physical necessity, the fact that if you are going to put something somewhere you need somewhere to put it, as a grammatical issue. But, that’s all somewhat by the by. The key thing here is that adjunct is not viable as a term in the synthetic grammar given that the linguistic ‘authorities’ differ in how they see its relationship to the notion of the adverbial.

6) Disjuncts and conjuncts are quite clearly defined, in part, by their semantic role: as we have seen, disjuncts express the speaker’s attitude to their sentence and conjuncts express discoursal relationships between sentences. But, linguists have clearly struggled to assign an overall semantic role to adjuncts. To get round this, they often list the semantic functions of adjuncts, as they see them. One such list I have come across offers the following semantic functions for adjuncts: causal, concessive, conditional, result, goal, instrumental, locative, measure, manner, modal, time. (In actual fact, it was apparent from the examples of the so-called modal function, which were of adverbs modifying verbs, that these were not separate parts of the sentence, and in that sense adverbials, but actually adverbs modifying the verb within the verbal part and these should not have been in the list at all.) The problem here is that lists are fine if they exemplify something that is already defined but not if they are how the item is being defined. What can readily happen is that the list is not complete and perhaps can never achieve completeness. What can happen is that one can come across individual items of language that don’t fit readily into any one semantic function in any of the created lists. For example, if one looks at the list of semantic functions of adjuncts above, one can readily think of adjuncts that don’t seem to be covered by it. A case in point is the word yes, which usually appears in sentences as a separate sentence part in its own right; it has a semantic function that is not covered by any of the semantic functions in the list above. The problem can apply across the whole tripartite distinction of adjunct, disjunct and conjunct: for example, what about an adverbial like In my opinion, what category does that fit into? It seems to stretch a point to call it a disjunct as it does not particularly express the speaker’s attitude to what they are saying; it’s not a conjunct because it does not necessarily indicate anything about the relationship of the current sentence to the previous one, and it’s hard to call it an adjunct as it does not fit readily into any of the categories often offered for the semantic functions of adjuncts.

Are adjunct, disjunct and conjunct useful categories to employ within a synthetic grammar ?

No.

__________________________________________________________

* Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, Oxford University Press, 2007